“The Emergence of Hopepunk in Poetry” by Nancy Lynee Woo (excerpts from MFA thesis for Antioch/LA, Winter/Spring, 2021)

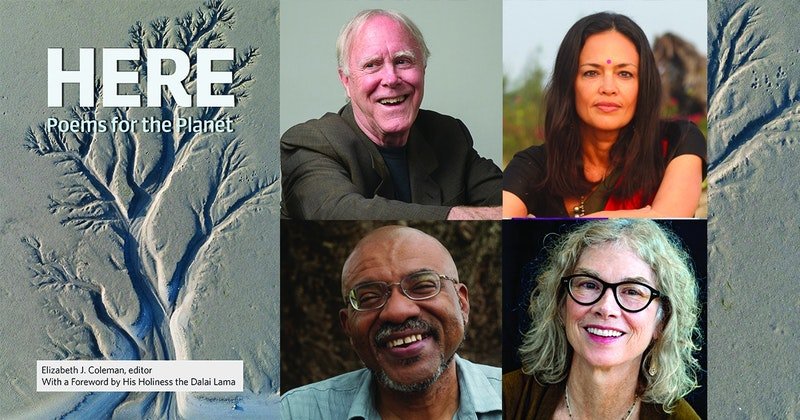

Elizabeth J Coleman speaking at AWP 2022

It was wonderful to meet Nancy Lynee Woo at the AWP 2022 panel I moderated entitled, “The Value and Use of Eco Poetry Anthologies in a Time of Environmental Crisis” and to read her terrific MFA thesis for Antioch/LA, “The Emergence of Hopepunk in Poetry, ” Winter/Spring, 2021.

According to Woo, citing science fiction writer Alexandra Rowland,

“Hopepunk is a technology of optimism, [that]…requires bravery and strength…It’s about standing up and fighting for what you believe in. It’s about standing up for other people. It’s about DEMANDING a better, kinder world, and truly believing that we can get there if we care about each other as hard as we possibly can, with every drop of power in our little hearts. ‘”

Woo says,:

The anthology HERE: Poems for the Planet (Copper Canyon Press, 2019, Elizabeth J. Coleman, ed.) is one …model I have found, which I think can and should be replicated and built upon. I found out about this book at a free Virtual Town Hall hosted by Poets & Writers California on April 6, 2021. His Holiness the Dalai Lama writes in the foreword to HERE, ‘We have to see humanity as one family and the natural world as our home…so it’s in our interest to look after it (Coleman xiii).

It is both a spiritual matter and a practical matter to take care of Earth, and this anthology is as much as a resource for the soul as it is a practical action guide for change. This dual purpose is what makes this collection so remarkable. Poems are more than art products; they are resources for our mental and emotional health as we continue the fight for social justice and environmental sustainability.

HERE was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2019, and seems to have been funded by a few hundred individual donors rather than grants or corporate interests. This seems significant as an example of collective action. The book is divided into six sections. The first five follow a typical anthology format of poems broken out over topics, such as ‘Where You’d Want To Come From: Poems for our Planet’ and ‘As If They’d Never Been: Poems for the Animals’ (Coleman vii, ix). The poems included are heartbreaking, inspiring, and full of immense talent, with voices like Gary Snyder, Mary Oliver, Robert Hass, Ross Gay, and Jane Hirshfield (Coleman).

There are some incredible moments captured in this anthology. As Jennifer Grotz writes in her poem ‘Poppies,’ which occurs in the first section, ‘Love is letting the world be half-tamed’ (Grotz 28). It takes a wild sort of imagination to bear the thought of rewilding, … a term from conservation biology that means restoring an area to its natural uncultivated state, including reintroduction of animals that have been driven out due to human activity and cessation of agricultural activities. The goal is to restore biodiversity and mitigate climate change .’ In every hopepunk narrative I’ve experienced, rewilding is at least one core tenet of the solution to prevent global ecological collapse…As Coleman writes in her introduction, ‘Addressing human injustice and discrimination, including racism and economic inequality…requires a livable earth’ (Coleman xv). She acknowledges environmental justice as part of the climate movement.

It is an underlying and implied theme in many hopepunk narratives that we as humans need to put aside our anthropocentric worldview in order to return to a more holistic and balanced state of life. The first poem in HERE by Catherine Pierce, simply called ‘Planet,’ alludes to this challenge in the line, ‘I’m trying to see this place even as I’m walking through it’ (Pierce 7). It is the hard work of hopepunk to change the way we see ourselves as a species, change the way we see ourselves as individuals relating to the natural world, and ultimately change the way we operate within our social and natural systems.

HERE offers reprieve from the hard work, as well, in poems like ‘The Peace of Wild Things,’ by Wendell Berry (HERE 40). Mother Earth can be a resource for us as we do the work to protect her. Berry reminds us of this when he says,

“When despair for the world grows in me… / I come into the presence of still water… / I rest in the grace of the world, and am free” (HERE 40).

We can restore ourselves within nature as we carry on the fight against its destruction, and in fact, rejuvenation is a key part of sustainability. We can “try to praise the mutilated world,” as Adam Zagajewski says in his poem with that line as its title (Zagajewski 45). These poems give us the hope inherent to hopepunk.

And it is poems like “Madwomen Shouldn’t Read the News” by Shara McCallum that gives us the punk (McCallum 48). She writes,

“But the day’s arrived, as deep down we knew / it would…our soon-to-be-extinction…the environment / churning into an apocalypse” (McCallum 48).

Speaking truth to power is and has always been a very punk thing to do, and the poem acknowledges that “the most skeptical” will say “I’m overreacting” (McCallum 48). And yet, the speaker speaks. It is this continued force of will that drives the punk in hopepunk; even when the climate deniers or racists call you crazy or put up an illogical and fearful defense against the truth, the hopepunk poets and storytellers keep writing.

Grief is always inherent to hopepunk. Paul Guest says he “grieve[s] to appropriate degrees” in “Post-Factual Love Poem” (Guest 49). and Nickole Brown laments what we have done to the animals, asking for forgiveness, asking “Am I not animal too?” in the poem “A Prayer to Talk to Animals” (Brown 98). Even through the grief, we can give thanks, as W.S. Merwin does in his poem “Listen,” where he writes

“with nobody listening we are saying thank you…/ dark though it is” (Merwin 83).

Hope drifts alongside the grief, gratitude alongside the pain.

And through the grief and pain, this anthology seems to be saying, in the words of Jane Hirschfield from her poem, “The Weighing”:

“The world asks of us / only the strength we have and we give it. / Then it asks more, and we give it” (Hirschfield 104).

We need to acknowledge the difficult feelings in order to move into action, again and again. We need to keep accessing a deeper well of capability inside us, because the alternative is unacceptable. This is what hopepunk asks of us. This anthology offers both reflection on deep feeling and catalyzation into action. Agency begins within, as shown in the poem “The Occupation,” by Robert Bringhurst, who puts forth,

“Our job…is not / to change the world – nor even keep it from changing. No…(the story / was over already): our only / job is being changed” (Bringhurst 153).

Hope begins within, so even if it is too late, it is on an individual level that we find the will, strength, and motivation to keep fighting for what we believe in with our “little hearts” (Rowland). And then the anthology gives us resources to do exactly that.

While the poetic content of the book shimmers with beauty, grief, and hope, that’s not quite what makes this collection groundbreaking. It is the combination of excellent writing and editing alongside a practical action guide that makes this book a model worth replicating. The last section is a 32-page advocacy guide compiled by the Union of Concerned Scientists urging community and political action to mitigate the effects of climate change (Coleman 191-223).

A brief introduction to the resource guide by Coleman urges us to manage our overwhelm and adopt a “ladder of engagement,” in other words, start small and keep taking step after step (191). The guide is formulated to give lots of different options for engagement to hopefully reach lots of different types of people; not everyone can do it all, but everyone can do something. As Coleman asserts,

“Since climate change and environmental destruction are caused by people, people can turn them around. We can and we must” (192).

Topics of advocacy include changing personal or household behavior to be more sustainable, communicating to others and inspiring others to take action, making sustainable purchasing decisions, reaching out to political representatives, leveraging social media, protesting, performing public education, connecting with the media, strategically organizing events, and collaborating with indigenous or environmental organizations for greater impact, among others.

HERE succeeds in doing something I have been seeking a model for: successfully using poetry as a catalyst for social change using direct action as a guide. Coleman reminds us,

“…it's important for us to recognize that the earth is facing multiple dire threats, with potentially irreversible impact... But even as we grieve, we act” (xvi).

The actionable appendix moves poetry from the world of art for art’s sake into the world of art in tandem with activism.

As Coleman writes,

“Poetry speaks to us and changes us as nothing else can” (xviii). While I’d say this statement is slightly hyperbolic, poets are nothing if not great exaggerators. Like some of the best hopepunk narratives, the end of the world is an exaggerated story—and framing climate change as an apocalyptic drama helps our lizard brains feel the urgency within time, especially as we go about our daily lives, which, for many, don’t feel very environmentally urgent.

So, in order to raise awareness and create a sense of urgency, we need exaggeration. Shock and awe in both narratives and poetry can help us process the severity of the threats on the temporal horizon, so that we all may make the small, unsexy changes necessary to prevent future catastrophe while tending to the current crises, such as more low-level flooding, increased severity of storms, growing droughts, and global pandemics. Time is the abstract concept that hopepunk helps condense into a felt takeaway: the apocalypse is not some distant story. It is happening currently, now, and we need to do something about it.

As Coleman says,

“Any action we take to slow environmental degradation is positive” (191). And she encourages us, “Even a small action taken by each reader who is touched by this volume could influence other people and positively impact our world. We're skipping a stone into the sea, with the hope that it will ripple outward into the future” (xvii). This action-no-matter-what energy is a core tenet of hopepunk, which reminds us we must act, rather than fall into inaction borne of despair or denial.”

Nancy Lynée Woo is a poet, educator, and community organizer. As a 2022 Artists at Work fellow, she brings arts programming to community gardens. Previously, she has received fellowships from PEN America, the Arts Council for Long Beach, and Idyllwild Writers Week. Nancy is the author of two chapbooks, Bearing the Juice of It All (Finishing Line Press, 2016) and Rampant (Sadie Girl Press, 2014). She has published poems in numerous journals and anthologies, including Tupelo Quarterly, The Shore, Radar Poetry, and Stirring.

As the founder of Surprise the Line, a community poetry workshop, she believes in the power of the arts to bring people together. Nancy has an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University, Los Angeles, and a BA in sociology from UC Santa Cruz. Her work is largely inspired by the magic and power of the natural world. Find her cavorting around Long Beach/Tongva, California, and online at @fancifulnance on social.